Who remembers the Magic Eye craze from the 1990s?

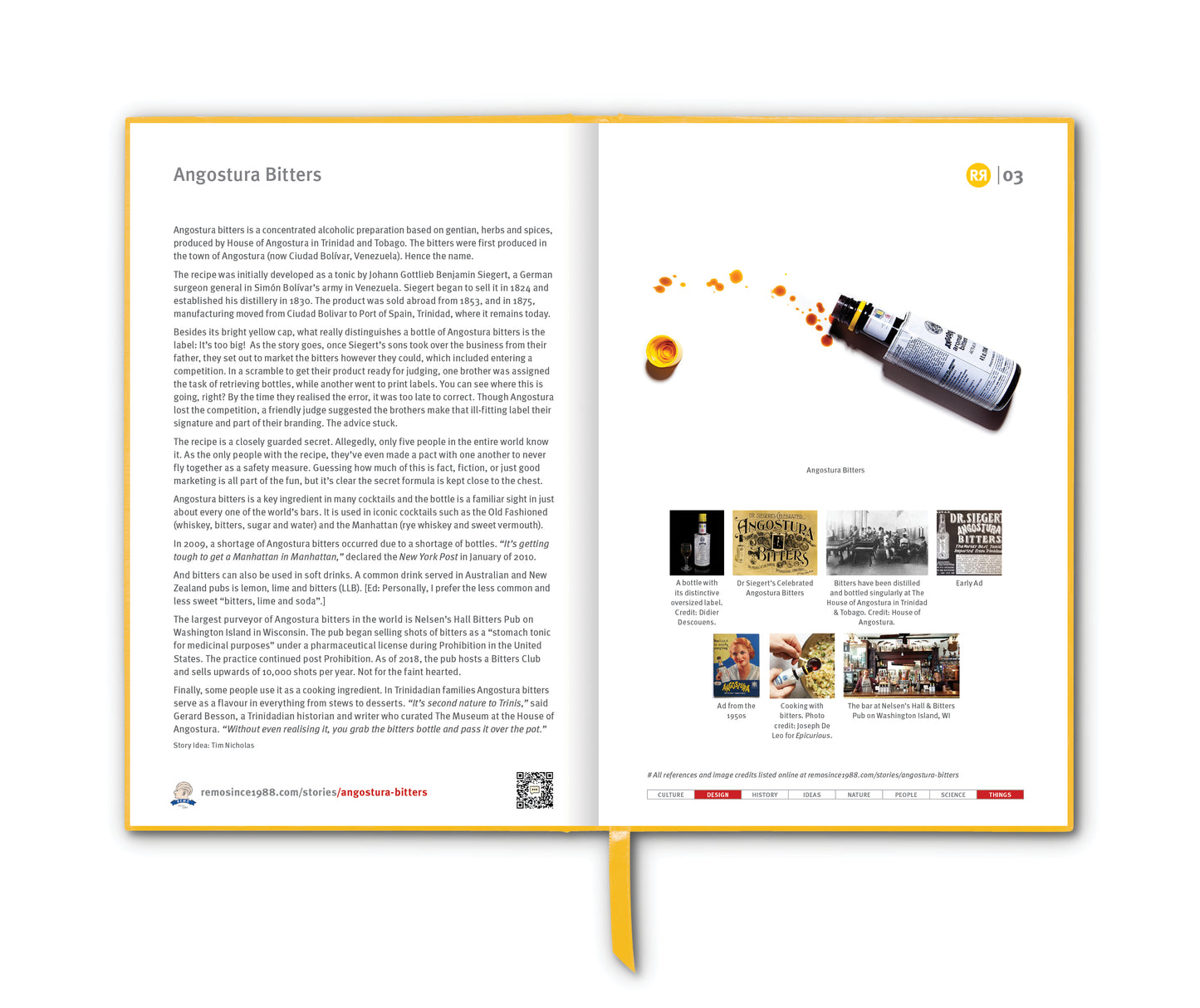

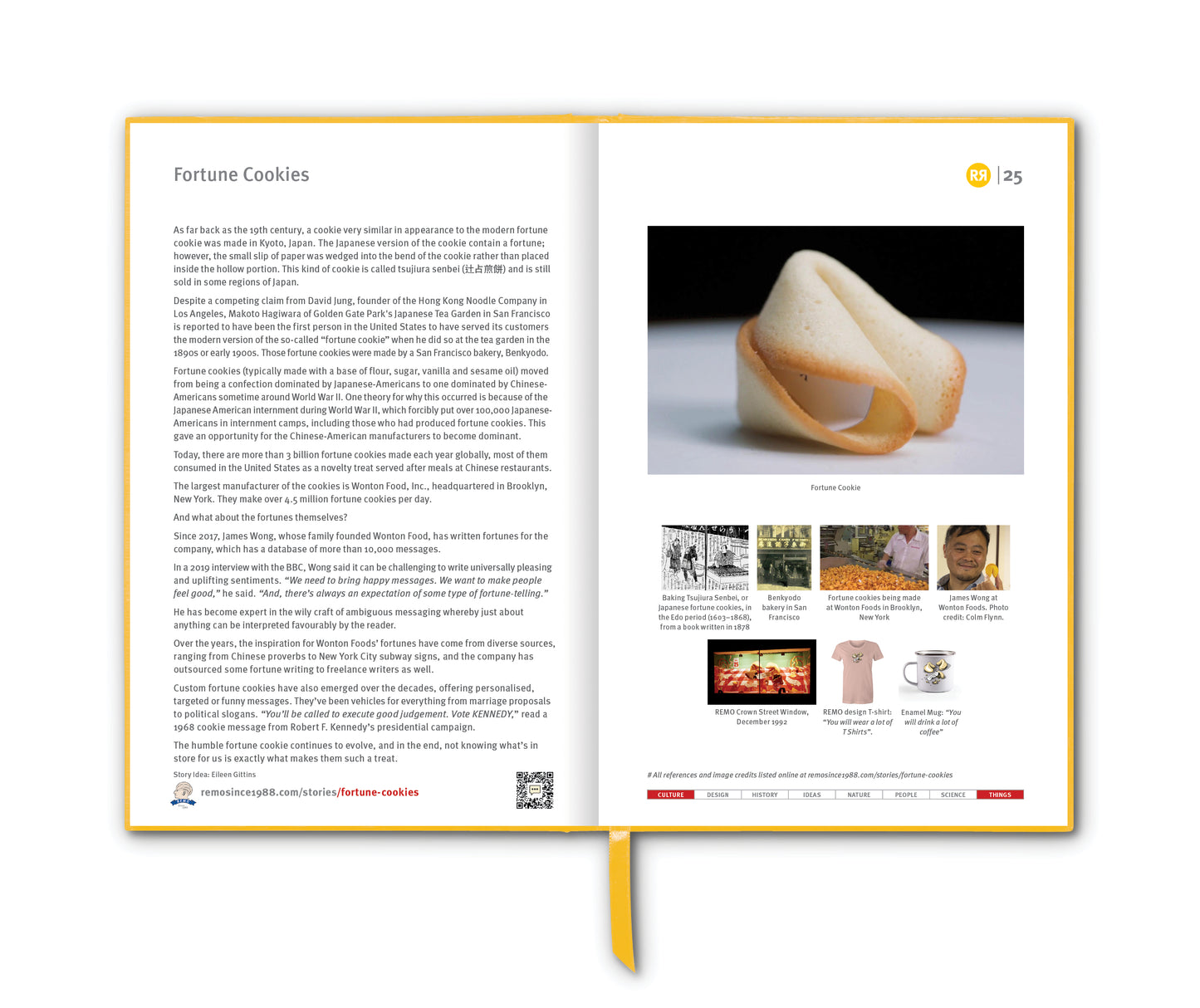

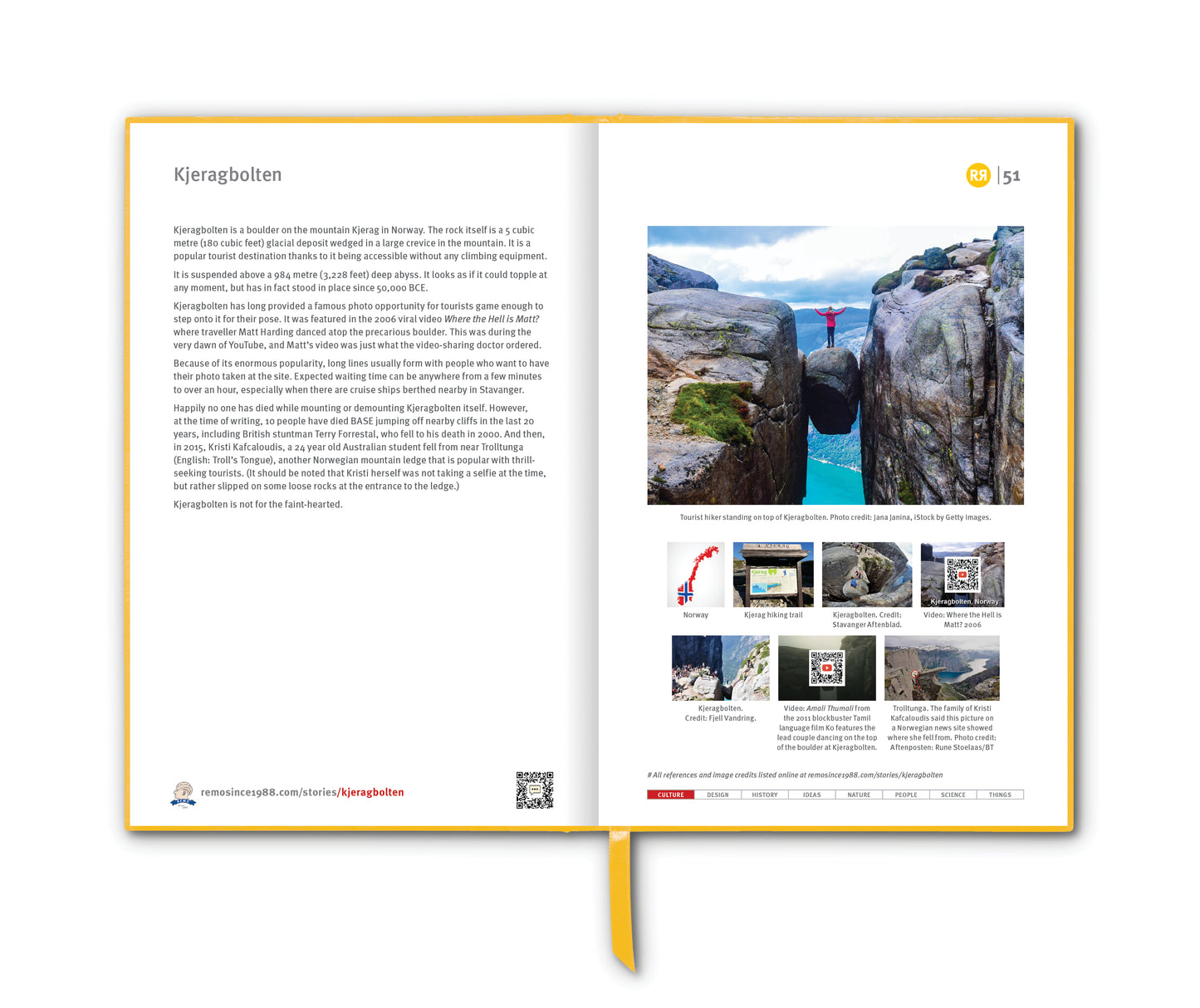

Stereograms, sometimes referred to as “autostereograms”, are optical illusions that allow a viewer to perceive a three-dimensional image from a two-dimensional pattern. These illusions are rooted in the concept of binocular vision, where the brain fuses two slightly different images from each eye to create depth perception. There are a number of different techniques that enable you to “see” the 3D image. Maybe the easiest is where you put your nose up against the image and then gradually move yourself further away until, at one point, the 3D image will switch into view. Try it with this image, and see if and when you can see the squirrel holding the nut?.

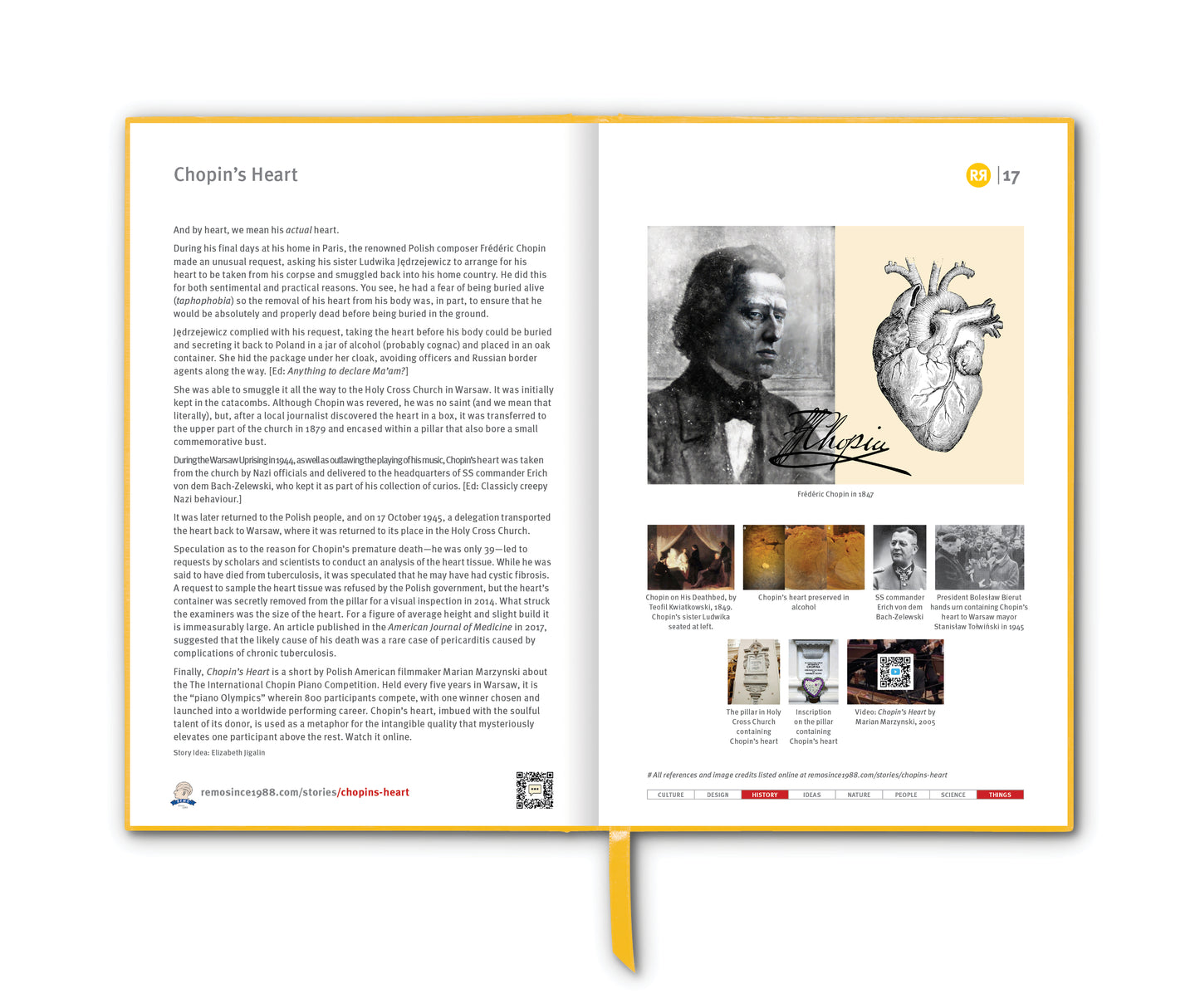

The concept of stereoscopy was first described by Sir Charles Wheatstone, a British scientist. Wheatstone demonstrated that the brain can perceive depth by combining two flat images, each viewed from a slightly different angle, to form a three-dimensional picture. He invented the stereoscope, a device that helped people view such stereoscopic pairs.

In the 1850s, Sir David Brewster, a Scottish physicist, refined Wheatstone's stereoscope to make it more portable and easier to use, popularising stereoscopic photography, which involved viewing 3D images using a stereoscope.

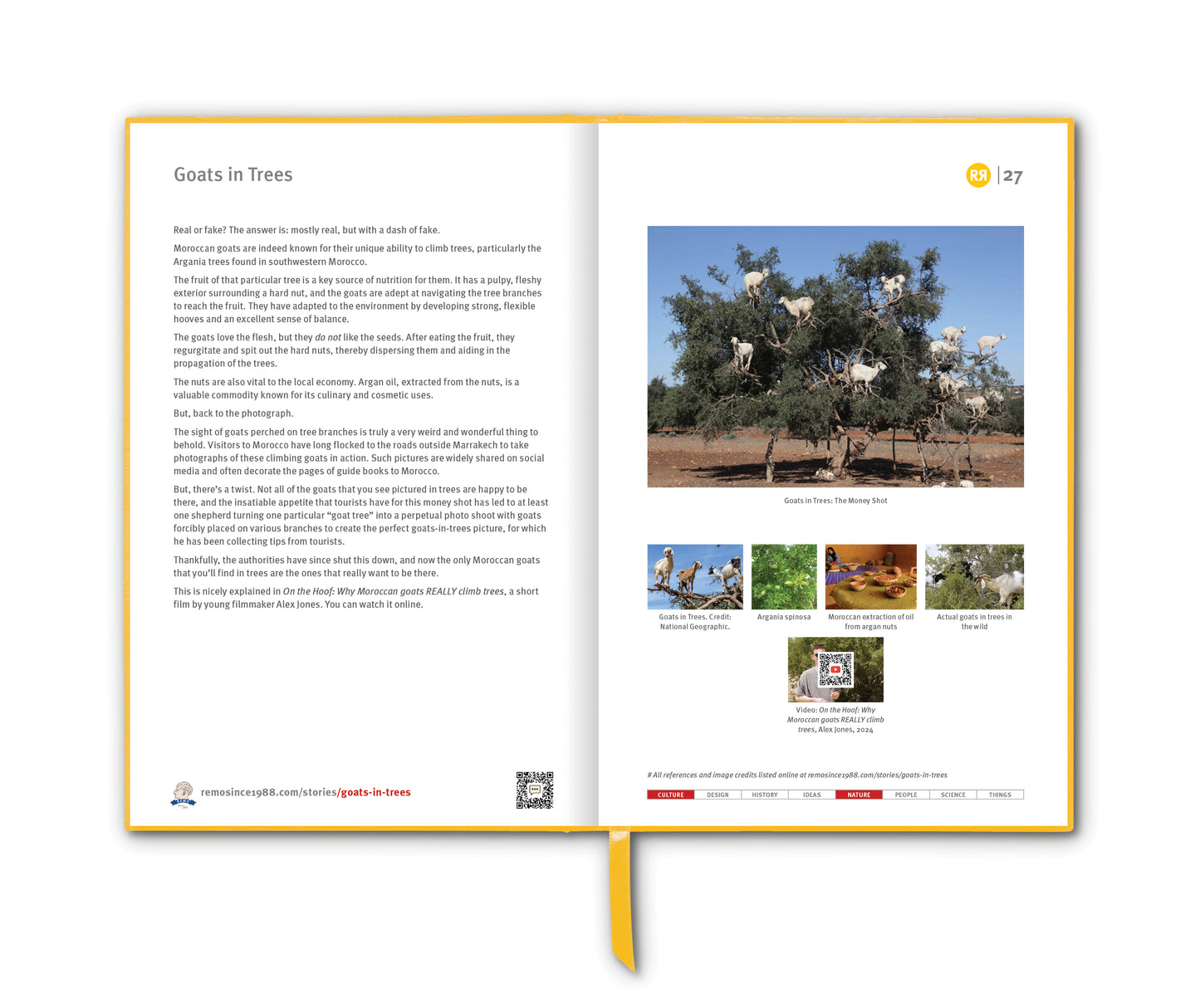

The View-Master system, introduced in 1939, four years after the advent of Kodachrome color film made the use of small, high-quality photographic colour images practical. Tourist attraction and travel views predominated in View-Master's early lists of reels.

The development of stereograms that do not require a stereoscope came much later. In the 1950s, Dr Bela Julesz, a neuroscientist and experimental psychologist, created random dot stereograms to study depth perception. These stereograms consisted of two patterns of random dots that, when viewed correctly, revealed a hidden 3D image. Julesz's work showed that depth perception is a function of the brain's interpretation of visual disparity, not just a feature of visual processing in the eyes.

Christopher Tyler, a neuroscientist and visual psychologist, took Julesz's concept further. In 1979 he invented the single-image random dot stereogram (SIRDS), which allowed a 3D image to be embedded in a single image, rather than requiring two separate images. This was the birth of what we know as the modern stereogram.

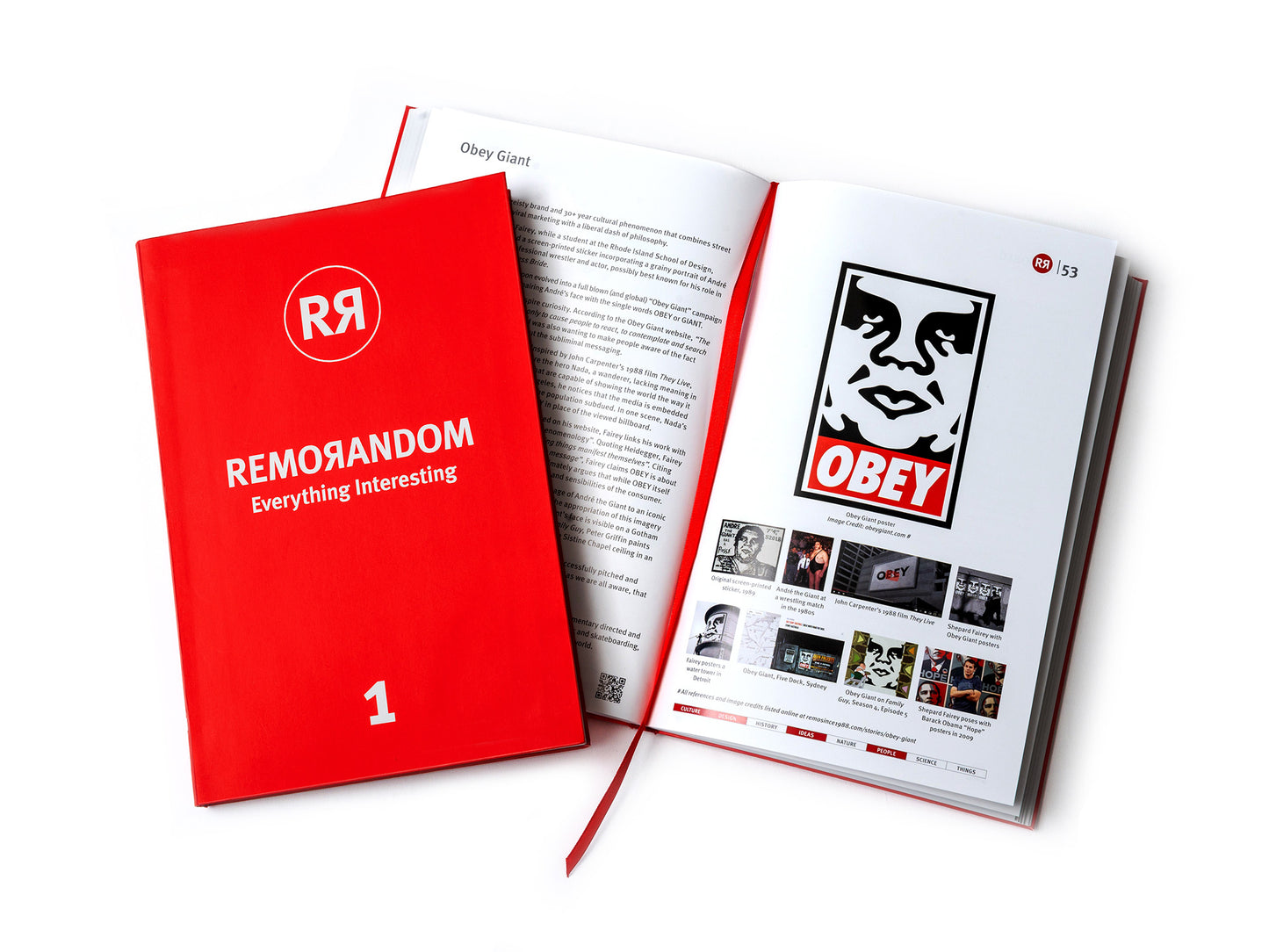

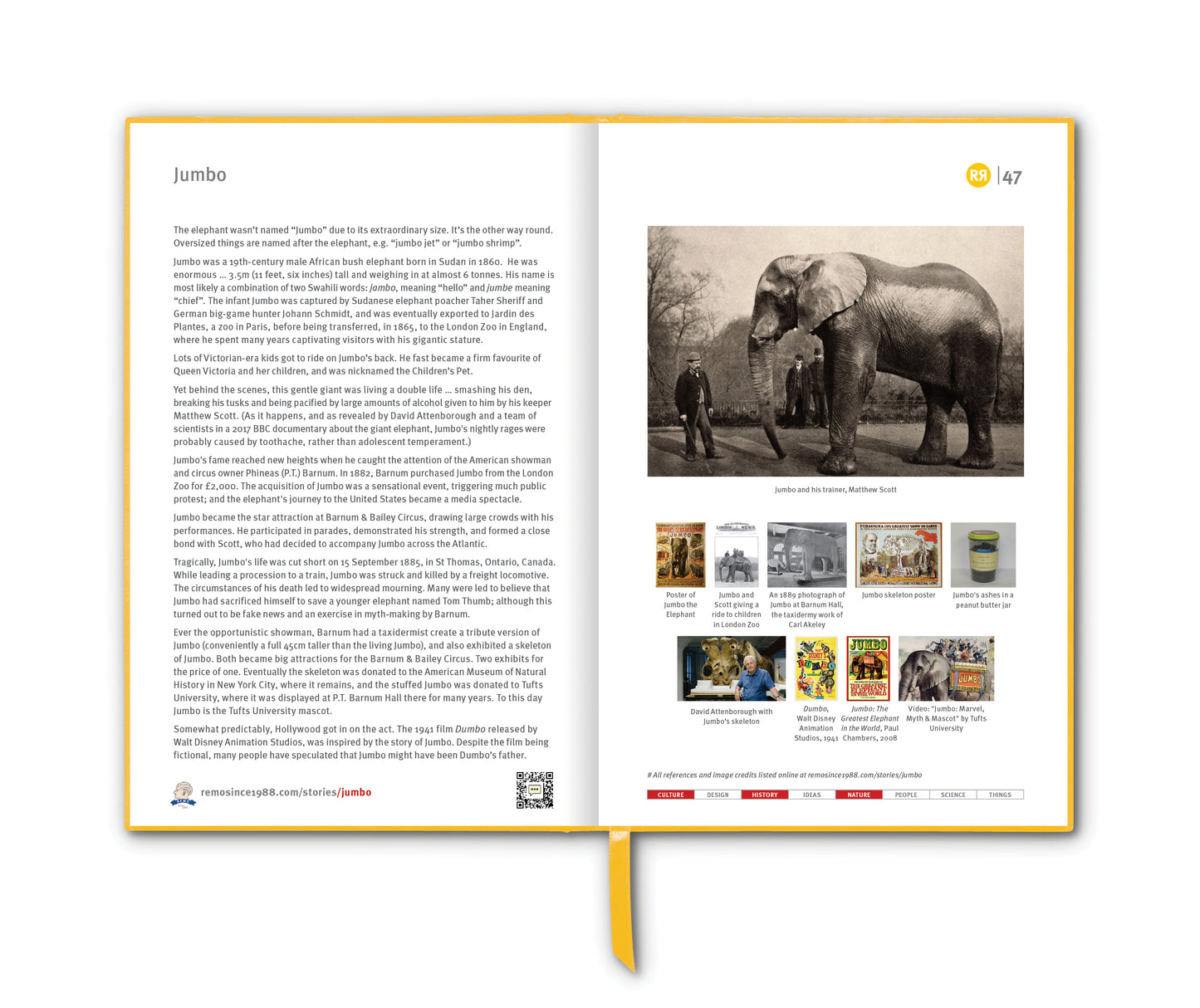

By the 1990s, stereograms gained widespread popularity through books and posters, most notably with the Magic Eye series, developed by Tom Baccei, Cheri Smith and Bob Salitsky. Magic Eye I, Magic Eye II and Magic Eye III became bestsellers and appeared on the New York Times Bestseller List for a combined 73 weeks. These colourful images became a cultural phenomenon, often sold in bookstores and malls, and people would gather to try to “see” the hidden 3D images.

Magic Eye posters became a social obsession. For a while there we were all staring intently at various 3D illusion posters. If one member of a group suddenly “got it”, the others would continue glaring in blurry-eyed frustration. [Ed: Ah … the 90s.]

Stereograms remain popular for their visual appeal and as a means of testing depth perception. They are used in eye exercises and visual therapy, as well as in artistic and recreational contexts. They have also been incorporated into some virtual reality (VR) technologies and used in scientific studies exploring vision and cognitive processing.

There are lots of stereogram galleries online. HERE is one that even enables you to create your own.

_________________________

References

wikipedia.org/wiki/Autostereogram

magiceye.com

hidden-3d.com

mentalfloss.com/article/622658/when-magic-eye-pictures-ruled-world

easystereogrambuilder.com

eyetricks-3d-stereograms.com/how_stereograms_work

Images

1. Stereogram reveals squirrel holding nut. Credit: 3Dimka for Hidden-3D.com

2. Old Zeiss pocket stereoscope with original test image

3. Brewster-type stereoscope, 1870

4. View-Master, 1939

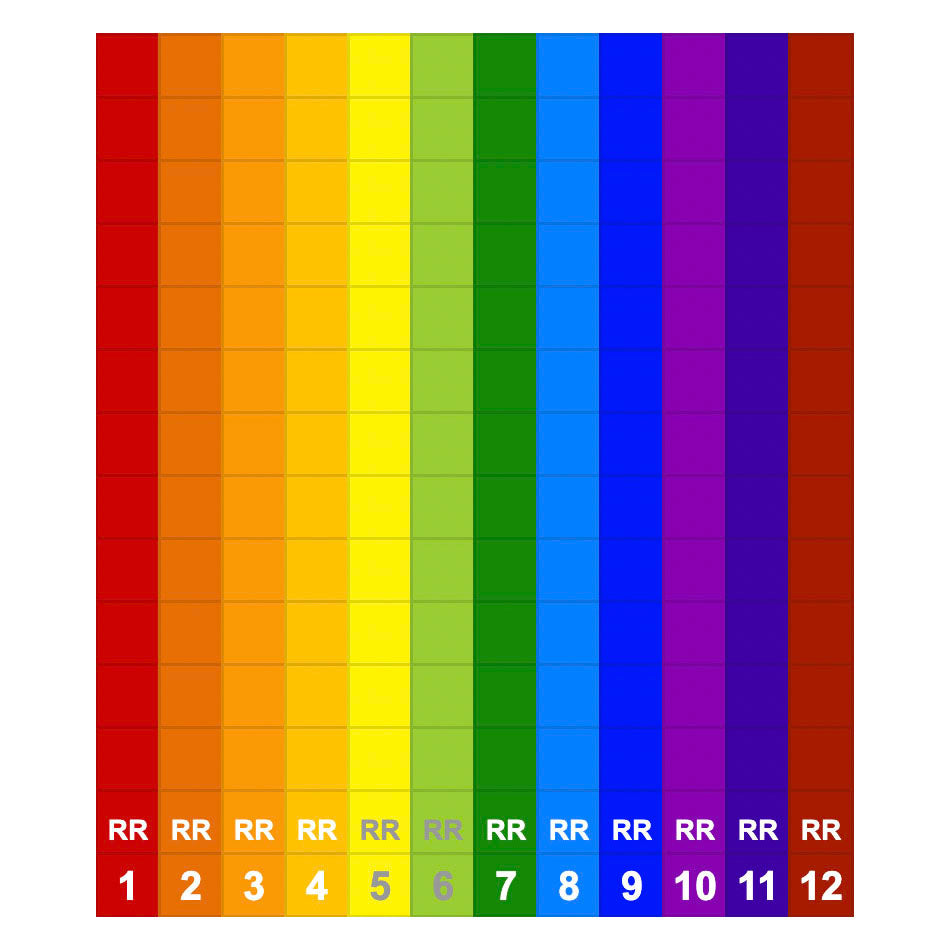

5. Stereogram reveals map of the world

6. Credit: eyetricks-3d-stereograms.com

7. Magic Eye books I, II and III appeared on The New York Times Bestseller List for a combined 73 weeks

8. Stereogram reveals fish tank