The Shape that Shouldn’t Exist

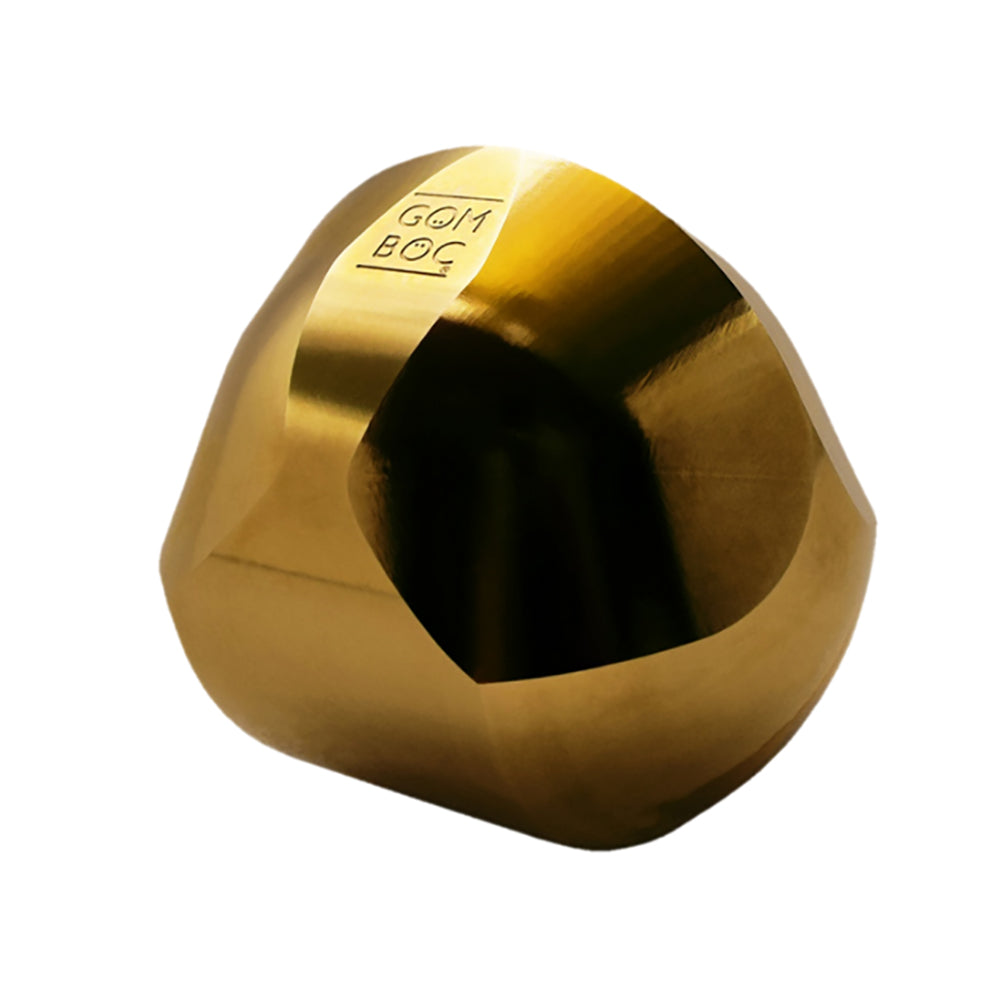

Have you ever wondered how a dome-shelled tortoise turns itself back the right way up when placed upside down (a survival reflex known as “self-righting”)? It’s because its shell resembles a Gömböc (pronounced goemboets), the first-known three-dimensional homogenous object that has just one stable point and one unstable point of equilibrium when placed on a flat surface.

The study of objects and their points of equilibrium dates back to the Greek polymath Archimedes. For the best part of the 20th Century, it was believed that the minimum number of points of equilibrium that a homogenous solid could have was four. However, in 1995, Russian mathematician Vladimir Arnold shook things up with his proposition that perhaps a convex object could exist with just two points of equilibrium.

The hunt for a homogenous mono-monostatic object (that is to say, a physical body that has both one stable point and one unstable point with an even density throughout) was taken up by a plucky Hungarian scientist by the name of Gabor Domokos. For ten years, Domokos hacked away at the problem in relative solitude … aside from a summer holiday in Rhodes where he enlisted the help of his wife to collect and classify 2,000 pebbles by the number and type of equilibrium points each stone had. He hoped that they would find one pebble with one stable and one unstable point. They didn’t.

So after ten years of solo searching to no avail, Domokos joined forces with fellow Hungarian scientist Péter Várkonyi. And within one year, by 2006, the two were able to find a mathematical solution: a homogenous object that resembles a softly pinched sphere. The two named their prized discovery Gömböc, a play on the Hungarian word “gömb” which means “sphere.” The presence of only one stable and unstable point in a Gömböc means that it will always return to a balanced state no matter how it is pushed around. To put it playfully, it acts like a Roly Poly Toy (also known as a Comeback Kid or Weeble) except that the Gömböc is not weighted. It is of an even density throughout.

It took some time to produce a physical solution as the tolerance for error was so minimal that even the most precise 3D printers couldn’t handle it. The scientists then developed a second solution, with greater margins for imprecision in printing, and gifted the first functioning physical Gömböc (with the serial number 001) to Vladimir Arnold on his 70th birthday. (You can actually buy inventor-sanctioned Gömböcs HERE.)

You might be thinking: “Cool! But what on earth is a Gömböc good for?” The initial answer might be “not much” but, as per the iterations of Domokos and Várkonyi, sometimes beauty isn’t to be found in purpose, but rather in the questioning and the philosophy that led you there. More than anything, the story of the discovery of the Gömböc is a lesson in patience (like that required to collect 2,000 pebbles) and sitting with the discomfort of the unknown. It shows that, in the world of science, questions are often a lot more valuable than answers. As Domokos himself said, “the discovery of something is exciting, but it’s much more exciting to think about something for an extended period of time!”

Having said this, the Gömböc has impacted a bunch of interesting things, motivating the development of a geometrical theory with applications ranging from biology through palaeontology to geophysics and planetology. The Gömböc shape has driven cutting-edge innovation in robotics and drug delivery (an insulin pill) and it inspired not only the development of the simulation software for the sailing yacht winning the 2017 America’s Cup, but also the work of leading contemporary conceptual artist Ryan Gander.

__________________________

References

wikipedia.org/wiki/Gömböc

gomboc-shop.com/#about

plus.maths.org/content/gomboc-object-barely-exists

the-gist.org/2018/06/the-tortoise-and-the-mathematician-a-tale-of-geometry

gomboc.eu/en/the-gomboc-and-americas-cup

Images

1. Gömböc. Image Credit: Domokos.

2. Indian Star Tortoise. The shape of the Indian star tortoise resembles a Gömböc. This tortoise rolls easily without relying much on its limbs.

3. Vladimir Arnold. Photo: Yuriy Ivanov/RIA Novosti.

4. Gömböc Structure. Structure of the characteristic Gömböc by Domokos and Várkonyi. Credit: vierkantswortel2.

5. Péter Várkonyi with Gabor Domokos. Still of the two collaborating Hungarian engineers taken from the video: “GÖMBÖC - The Beauty of Thinking | Márton Szirmai”. Watch on Vimeo HERE.

6. The cover of the 2006/4 issue of the Mathematical Intelligencer

7. Statue of a Gömböc by József Zalavári, 2017 Budapest, Hungary. Image Credit: Kicsinyul.

8. Gömböc-Inspired Insulin Capsule. Working scheme. Reprinted from AAAS (American Association for the Advancement of Science).

9. Ryan Gander, The Self Righting of All Things. Lisson Gallery, London (2 March–21 April 2018). Photo: Jack Hems.